Carved with a hatchet….naturally

From Dostoevsky to Burroughs to pulp sci-fi, Ian Curtis devoured offbeat literature.

Jon Savage via the Guardian

In March 1980, Joy Division released their third single, featuring the songs “Atmosphere” and “Dead Souls”. Published in a limited edition of 1,578 on an independent French label, Sordide Sentimental, this was no ordinary record. Carrying a “warning” of one word – gesamtkunstwerke – it was, indeed, a total artwork comprising graphics, music, photographs and text, a world unto itself.

On the cover of the fold-out was a painting by neoclassical artist Jean-François Jamoul, picturing a robed hermit looking out over mountain tops, the valleys obscured by clouds. Inside was a collage of a lone figure descending into the depths of the earth, with Anton Corbijn’s photo of Joy Division under strip lighting in Lancaster Gate station. And then there was the text.

In the essay entitled “Licht und Blindheit” (light and blindness), Jean-Pierre Turmel positioned himself as far away from rock crit cliché as possible. Citing Pascal, Heinrich von Kleist and Georges Bataille among others, he went in deep in his attempt to explain the effect that Joy Division had on him:

“At the heart of daily punishment and sufferings, in the very wheels of encroaching mediocrity, are found both the keys and the doors to inner worlds.”

Received with rapture by Joy Division fans – not least because the two songs were among the best the group ever recorded – the Sordide Sentimental single was an early recognition of the fanaticism, if not religiosity, that would surround the group. Ian Curtis loved the package, but then he above all knew how words and books worked as a threshold into other dimensions.

In the same way that Jim Morrison referenced Louis-Ferdinand Céline’s Journey to the End of the Night in the Doors’ moody masterpiece, “End of the Night”, Curtis dropped hints in song titles such as “Dead Souls”, “Colony” and “Atrocity Exhibition” that he had read writers as diverse as Gogol, Kafka and Ballard, while the lyrics reflected, in mood and approach, his interest in romantic and science-fiction literature.

This is not to legitimise Curtis’s lyrics as literature, but to make the point that, in the 60s and 70s, pop culture acted as a clearing house for information that was occult in the widest sense: esoteric, degraded, unpopular, underneath the literary radar. And there was a whole subculture and a market that supported these endeavours to go underground, to step outside.

Joy Division continue to inspire new generations of listeners, but they were very much a product of time and place. Ian Curtis was an avid reader who became a driven writer “trying to find a clue, trying to find a way to get out”. In the north-west of England in the mid to late 70s, he found the materials that he needed for his escape, only to discover that – as was evident from much of his reading – escape was impossible.

Like the Doors and the Fall, Joy Division were named after a book. Their inspiration was not Huxley or Camus, however, but a piece of Holocaust exploitation. The House of Dolls by Ka-Tzetnik (real name Yehiel Feiner) told of the areas in concentration camps in which women were forced into sex slavery: not the Labour Division but the Joy Division. By 1978, when the group adopted their name, the novel/memoir had sold millions of copies in paperback.

The early to mid-70s was a golden age of paperback publishing, both high and low. Apart from Penguin, with its vigorous science-fiction line that included authors such as Philip K Dick, Olaf Stapledon and JG Ballard, there were Picador, Pan, Mayflower, Paladin – the last with a wide-ranging list that included Jeff Nuttall and Timothy Leary. Selling for 50p and upwards (when an LP cost £3.25), these books were readily available to young minds.

In the Manchester area, there were several outlets for this jumble of esoterica, some left over from the oppositional hippie days. The historian CP Lee remembers shops such as Paper-chase and the leftwing Grassroots, while Paul Morley worked at the Bookshop in Stockport: “Tolkien was a huge seller, war books too, lots of experimental science fiction, as well as the Mills & Boon romances and tucked-away soft porn that kept things ticking over.”

Then there were the shops run by David Britton and Mike Butterworth: House on the Borderland, Orbit in Shudehill and Bookchain in Peter Street, just down the road from the site of the Peterloo massacre. As Butterworth recalls, all three “were modelled on two London bookshops of the period, Dark They Were and Golden Eyed in Berwick Street, Soho – which sold comics, sci-fi, drug-related stuff, posters, etc – and a chain called Popular Books”.

With his friend Steven Morris, Ian Curtis regularly visited House on the Borderland. Butterworth remembers them as “disparate, alienated young men attracted to like-minded souls. They wanted something offbeat and off the beaten track, and the shop supplied this. They probably saw it as a beacon in the rather bleak Manchester of the early 70s.”

“They came in every couple of weeks, sometimes more often. Ian bought second-hand copies of New Worlds, the great 60s literary magazine edited by Michael Moorcock, which was promoting Burroughs and Ballard. My friendship with Ian started around 1979: we talked Burroughs, Burroughs, Burroughs. At the bookshops he would have been exposed to an extremely wide range of eclectic and weird writers and music.”

Dropping out of school at 17, Curtis was an autodidact who took his cues from the pop culture of the time. In 1974, David Bowie was interviewed with William Burroughs in Rolling Stone. The actual chat was fairly non-eventful, but it made the link explicit – especially when Bowie was seen fiddling with cut-ups in Alan Yentob’s “Cracked Actor” documentary – and Burroughs would cast a major shadow over British punk and post-punk.

In the mid-70s, there was a sense – reinforced by the vacant, derelict state of Britain’s inner cities – that the bomb had already dropped. With its casual brutality and black humour, Burroughs’s accelerated prose – what his biographer Ted Morgan called his “nuclear style” – matched this apocalyptic mood. The lack of conventional narrative in his books plunged the reader into a maelstrom of malevolent, unseen forces and ever-present, unidentified dangers.

Joy Division rarely did interviews. In January 1980, however, they gave an audience to the young writer and singer Alan Hempsall. This was to be the only time that Curtis talked about his reading, and he mentioned Naked Lunch and The Wild Boys as two of his favourite books. The group had recently encountered Burroughs at their Plan K show in October 1979, though when Curtis approached the author to get a free copy of The Third Mind, he was rebuffed.

Curtis began writing in earnest during 1977, when he and his wife Deborah moved into their Barton Street home. In her memoir, Touching from a Distance, Deborah Curtis remembers that “most nights Ian would go into the blue room and shut the door behind him to write, interrupted only by cups of coffee handed through the swirls of Marlboro smoke. I didn’t mind the situation: we regarded it as a project, something that had to be done.”

His first attempts showed a writer struggling to establish a style. One of Joy Division’s most effective early recordings, “No Love Lost”, contains a spoken word section that lifts a complete paragraph from The House of Dolls. Songs such as “Novelty”, “Leaders of Men” and “Warsaw” were barely digested regurgitations of their sources: lumpy screeds of frustration, failure, and anger with militaristic and totalitarian overtones.

Like the group, Curtis worked hard to improve. His keynote early song for Joy Division, “Shadowplay”, explored for the first time the territory that he would make his own. Like a Burroughs cut-up, the lyrics shifted from a direct address to a description of a situation – often horrific or unsettling: “the assassins all grouped in four lines” – sealed with a first-person confession of guilt or helplessness: “I did everything I wanted to / I let them use you, for their own ends.”

By then, Curtis was exploring more than pulp horror. Deborah remembers him reading “Dostoevsky, Nietzsche, Jean-Paul Sartre, Hermann Hesse and JG Ballard. Photomontages of the Nazi Period was a book of anti-Nazi posters by John Heartfield, which documented graphically the spread of Hitler’s ideals. Crash by JG Ballard combined sex with the suffering of car accident victims.” Another favourite was Ballard’s 1975 High-Rise.

Deborah recently recalled that Ian never read these books in her presence, which she felt was “an indication to me that he considered them part of his work. They were important to him. It wasn’t something he did as relaxation or for pleasure. He was studying/working. Too important to try and concentrate on with someone else in the room. It wasn’t something he did as relaxation or for pleasure. His books would be on the floor next to his drafts.”

At Joy Division rehearsals, Curtis would act as the director, spotting riffs and working with Bernard Sumner, Peter Hook and Stephen Morris to turn them into songs. Once the music was completed, he would dig into the plastic bag in which he kept his notebooks and begin fitting words to music. As Sumner remembers in the film documentary Joy Division, “he would just pull some words out and start singing them, so it was pretty quick”.

Between 1978 and 1980, the lyrics poured out of him, enough for three albums and more. Curtis did not seek conventional narratives, but strived instead to create a situation in which the emotion came from the response of the narrator. As the lines shifted from the universal to the personal, the “I” was often trapped, as in a Greek tragedy, by forces outside his control: “We’re living by your rules, that’s what we’ve been shown” (“Candidate”).

Like many young men, Curtis oscillated between feelings of omnipotence and abjection, and his lyrics reflected this. The sense of a hero struggling – perhaps in vain – within a labyrinthine system is a common theme in Kafka, Gogol and Burroughs, among others. It’s not hard to see a thematic line from Kafka’s Control Officials (The Castle) to Burroughs’s theories of Control, or from the fatalism of the 19th-century Russians to postwar science fiction.

Ballard’s exquisite techno-barbarism offered a twist. Science fiction offers an alternative present, and Curtis used this language on Joy Division’s first album, Unknown Pleasures. Songs such as “Interzone” place desperate and forgotten youth, like the Wild Boys, in empty Mancunian landscapes. At the same time, there was a preoccupation with religious imagery and martyrdom, combined with a Nietzschean aloofness.

The words were, of course, only part of the package. Joy Division were a total artwork, right down to the record sleeves, the clothes and their posters. Live, they were brutal and impossibly intense: as a front man, Curtis placed himself completely in the moment with a persona that, intentionally or not, approximated the faraway stare of a seer: “I’ve travelled far and wide through many different times” (“Wilderness”).

It’s not hard to see how Curtis would have identified with the civil servant hero of Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground, with his nihilistic disdain for the human “ant hill”: “We are born dead”. The problem of rock music is the idea of authenticity, the requirement that a front man should act out, if not embody, lyrics and mood. As Joy Division took off, he became trapped by his own script: “This life isn’t mine” (“Something Must Break”).

In the pivotal “Atrocity Exhibition”, Curtis wrote: “for entertainment they see his body twist / Behind his eyes he says, ‘I still exist'”. Though it refers to Ballard’s novella, the mood of the song is much more like Hermann Hesse’s Steppenwolf. When asked about this by Alan Hempsall in January 1980, Curtis replied that he’d written the song long before he’d read the book: “I just saw this title and thought that it fitted with the ideas of the lyrics.”

It seems clear that Curtis used his books as mood generators. At the same time, his wife thought “the whole thing was culminating in an unhealthy obsession with mental and physical pain”. As she recently wrote: “I think that reading those books must have really nurtured his ‘sad’ side.”

As 1979 turned into 1980, Curtis’s mood grew darker. “Dead Souls” was a slice of HP Lovecraft horror, old and cold, that made the hairs stand up on your neck. Songs from the Closer period, such as “Isolation” and “Passover” – “this is the crisis I knew had to come” – showed the lyrical balance tipping into outright, anguished confessional. With its key words “will” and “again”, “Love Will Tear Us Apart” spoke of recurring emotional torment.

Nobody picked up the obvious signs. Tony Wilson, who is interviewed in the documentary, claimed he thought they were “just art”. Curtis’s final lyric, “In a Lonely Place”, echoes Jean-Pierre Turmel’s description of Bernini’s Ecstasy of St Teresa: “the marble, ghastly pale, set the body in a specific moment, between flesh and crystal, just before the tangible disappears and the soul flies away”.

Curtis’s great lyrical achievement was to capture the underlying reality of a society in turmoil, and to make it both universal and personal. Distilled emotion is the essence of pop music and, just as Joy Division are perfectly poised between white light and dark despair, so Curtis’s lyrics oscillate between hopelessness and the possibility, if not need, for human connection. At bottom is the fear of losing the ability to feel.

Nearly 30 years after his death, Joy Division have gone mass market: their music crops up in Coronation Street, or as a soundtrack for BBC sports coverage. I’m pleased the songs are receiving their due, but it’s also worth restating that the band, and its lyricist, were products of a particular time in cultural history, when there was an urge to read a certain sort of highbrow literature, and when intelligence was not a dirty word.

Häxan is a 1922 Swedish/Danish silent horror film written and directed by Benjamin Christensen. This version was updated in the mid 1960’s to include an English narration by William S Burroughs.

Based partly on Christensen’s study of the Malleus Maleficarum, a 15th-century German guide for inquisitors, Häxan is a study of how superstition and the misunderstanding of diseases and mental illness could lead to the hysteria of the witch hunts. The film was made as a documentary but contains dramatized sequences that are comparable to horror films.

With Christensen’s meticulous recreation of medieval scenes and the lengthy production period, the film was the most expensive Scandinavian silent film ever made, costing nearly two million Swedish kronor. Although it won acclaim in Denmark and Sweden, the film was banned in the United States and heavily censored in other countries for what were considered at that time graphic depictions of torture, nudity and sexual perversion.

sunday morning

brings the dawn in

it’s just a restless feeling

by my side

early dawning

sunday morning

it’s all the wasted years

so close behind

watch out the world’s behind you

there’s always someone around you

who will call

it’s nothing at all

sunday morning

and I’m falling

I’ve got a feeling

I don’t want to know

early dawning

sunday morning

it’s all the streets you’ve crossed

not so long ago

watch out the world’s behind you

there’s always someone around you

who will call

it’s nothing at all

watch out the world’s behind you

there’s always someone around you

who will call

it’s nothing at all

sunday morning…

“An idea is a point of departure and no more. As soon as you elaborate it, it becomes transformed by thought.”

Pablo Picasso

The optical toy, the phenakistoscope, was an early animation device that used the persistence of vision principle to create an illusion of motion. It was invented by Joseph Plateau in 1841.The phenakistoscope used a spinning disc attached vertically to a handle. Arrayed around the disc’s center were a series of drawings showing phases of the animation, and cut through it were a series of equally spaced radial slits. The user would spin the disc and look through the moving slits at the disc’s reflection in a mirror. The scanning of the slits across the reflected images kept them from simply blurring together, so that the user would see a rapid succession of images that appeared to be a single moving picture. A variant of it had two discs, one with slits and one with pictures; this was slightly more unwieldy but needed no mirror. Unlike the zoetrope and its successors, the phenakistoscope could only practically be used by one person at a time.

Courtesy the Richard Balzer Collection

See more here @ the Richard Balzer Collection website

“Everything was alive like me on this earth, everything was breathing.” — Brion Gysin

The Hotel La Residence in Lyon was the place where we gathered for the retrospective of Brion Gysin’s art works at the Institut d’Art Contemporain in Villeurbanne. The show had transferred from the New Museum in New York and yet this was much more than a second run — it was absolutely appropriate that this important exhibition should take place in France, where Gysin had lived for so many years, and where he produced some of his greatest work. He had moved through the street life and high society of Paris, and had seen the city through all its changes, from his arrival in 1934, aged eighteen, with 15 dollars a month to live on, to his death in his apartment opposite the Beaubourg in 1986, at the age of seventy. There had been some wonderful, and also pretty terrible, times spent in Tangier and London, and many a “trip from here to there,” but there would always be Paris. For many years he felt ignored and dismissed by the art world, and this wasn’t so much because Paris was no longer the center of the art world, but because he was a progenitor post-modernist of the trans avant-garde, a traveller and internationalist, and an esotericist. He would always regard Tangier as his spiritual home, but he was, he said, a “terminal tourist.” The markets and institutions of the art world had shifted definitively to New York and London after the Second World War, but Gysin was always just passing through those cities where a profitable art career could have been developed. Instead, he was “unlocatable,” often when it most mattered, not leading “a painter’s life” at all, but pursuing other, magical interests. Because of the Beat Hotel years and his Paris exhibitions and his final years resident there after a definitive return in the mid 1970s, his life and work are inextricably tied to that city, that country. This show testified to both Gysin’s Francophile sympathies and to his love of North Africa, but it also validated his cultural and geographic marginality — a marginality now seen to be inextricably tied to his originality. The fated denizen of the Boho Zone had the vantage point of the visionary outsider.

Our group included friends of Brion Gysin — Terry Wilson, Udo Breger, Philippe Baumont — and fellow admirers of his art, including Axel Heil, Stephen Vassilakos, Jacki Ledevehat and myself. The manifestations were starting — the young people, enraged and engaged, walked down rue Victor Hugo past our hotel to the Place, followed by cops in their body armour, with their visored helmets and shields and batons — the confrontations were inevitable, Minutes To Go indeed. . . Within days an image of the riot-torn, tear-gassed streets of Lyon would appear on the front page of the International Herald Tribune, that essential touchstone of American ex-pats the world over — and source of key material for the cut-ups of Minutes To Go. On French TV we would see the same clips endlessly recycled to hammer home the idea not of nationwide protests and injustice but of “troublemakers” and “mindless thugs” — well, I’ve come across a few thugs in my time, but I never saw one with “Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité” painted on her face. Petrol stations were out of fuel or would very soon run out — “Workers cannot be deprived of gasoline,” said Sarkozy, as protesters brought traffic to a halt at energy “chokepoints,” truck drivers staged “escargot” protests on the motorways, railways were disrupted and the garbage piled up… 1,423 protesters, mostly young, would be arrested by the 21st… Could this be May in October? Clearly, Gysin’s retrospective was opening under “Riot Conditions”… At the vernissage, Gysin’s friend Catherine Thieck, who curated the 1987 Galerie de France show “Brion Gysin: Calligraphies, Permutations, Cut Ups,” said to Terry Wilson, “Isn’t it just like Brion to bring us all together in the suburbs of Lyon?” In fact, there was a direct correlation between those young people protesting against state legislation and the crowd of young people who appeared at the Gysin opening. Ramuntcho Matta, Francois Lagarde, Francois de Palaminy, Rosine Buhler, Terry and Udo and Philippe and many more were at the vernissage, and Gysin would have loved it that his old friends and admirers were joined by those young people, eager to see his work. Louise Landes Levi wrote to me, “Lyon scene sounds incredible, almost as if Brion made it happen, as a similar riot, the young & strong, broke out the last time I saw him read, at Beaubourg, he was attached to all kinds of tubes under his white robe, I panicked, feared for his life but I think he enjoyed himself, I am sure he was there for the riots.” We were just passing through, the riots and jams hardly touched us, but the media message was inescapable, and that ambience of things going askew, pressure building, we could feel it, and there was, too, a Gysin current coming through… We were talking about Gysin’s lack of recognition, how he was always himself passing through different cities and time zones, and a Bowie track suddenly blasted out from a boutique, an echo of the ambience of Brion Gysin’s later Paris nights, when he was hanging out at The Palace with Keith Richards and Iggy Pop and other rock-star art cognoscenti — it was the perfectly ironically titled, “A New Career In A New Town…” Already we were picking up on the “Gysin Level” as Burroughs dubbed it, and as Terry always refers to it, and it really felt like dub music, the reshaping and remixing of the existing recordings with echo, reverb, and delay, the rhythm and alliteration of Gysin’s work coming through from other sources, an audio and visual remix following us around Lyon and up to Paris and through the city streets, manifestations of a different order, jumping out of speakers and sprayed on city walls, breaking through TV monitors and leaking through newspaper formats and old photographs, and mirror apparitions and psychic photography — associations, connections, tracks we were helpless but to follow, it would have been foolish to do otherwise, a whole series of currents of meanings, political, personal, aesthetic, which we would track in the days following the show. We’d come to see the show, to look at the Gysins — and our trajectories did more than intersect, they radiated outwards and connected in ways which seemed premonitory and fateful, literally manifesting as the manifestations built in the streets and those riot clips were incessantly, ideologically recycled and reiterated. We would cut that media material up, intervening and disrupting the image flow, rewriting the script. In derives around Paris in the days and nights following the show’s opening we passed significant Gysin locations, and caught visual echoes of his calligraffiti on the walls, the past suddenly glimpsed, appearing in a new guise. Gysin’s work permeated the experience — but it was something more than art. I realized I was reviewing an exhibition, but also tracking the effects of an exhibition — something hardly ever acknowledged by art critics or reviewers. We were picking up on the show’s afterglow, tracing the psychic connections which Gysin’s work is all about… After all, that “immense revolutionary demonstration” which Gysin saw in his own painting, and those “street barriers” he discovered in his calligraphy, we’d seen them, too, in the retrospective at Villeurbanne, and now here they were “for real” on the streets of French cities and as a running script on continual replay through the 24 hour media (we switched the sound off, we knew what those commentators and politicians were saying). A couple of days after the Gysin show, strolling down the Rue du Bac in Paris, Terry said, “Well, the manifestations haven’t ruffled any feathers around here.” The next second a very small man walked past us in boots and knee socks and a Tyrolean hat with two one-foot high feathers sticking up in the air from his hat band. He patted Bouddha on the head and disappeared. Such Gysinian manifestations had occurred in New York, too, with the sudden miraculous appearance, shortly before the show, of the missing eighth painting in Gysin’s beautiful 1961 series of calligraphic acrylics, whereabouts previously unknown. And Laura Hoptman, curator of the retrospective, told Terry that a very impressive, regal figure, dressed entirely in white, walked back and forth in front of the New Museum in the days before the show, as if safeguarding proceedings, his very presence casting a mysterious protective radiance. He did not speak to anyone and he didn’t enter the museum. “Brion’s representative, clearly,” Terry said.

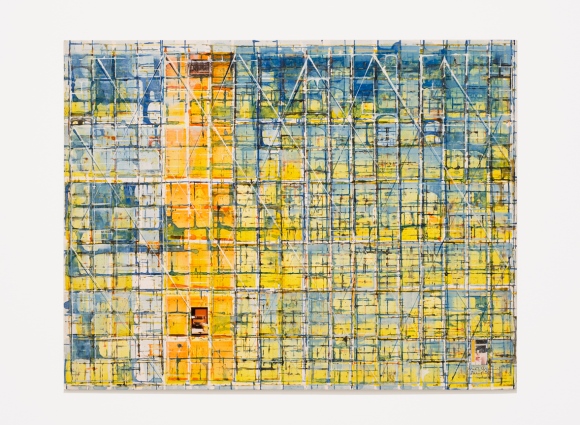

In the last twenty years there have been fine shows of Gysin’s work, in particular at the October Gallery in London, which supported his work while he was alive and has continued to do so, but this retrospective provided an unparalleled overview, despite certain curious omissions such as the renowned multiple-image Marrakesh paintings of the late 1950s, and his big late picture Calligraffiti of Fire. The absence of the Marrakesh pictures was particularly baffling and unfortunate since these have always exerted a powerful fascination on viewers and their conjuration of shifting, elusive images is one of Gysin’s most original achievements. For those who had never seen the originals, it was a real loss. Still, the exhibition was an opportunity to get a sense of the work over forty-five years, from the 1940s decalcomanias to the final photo-grids of the 1970s. Several Third Mind scrapbooks, made with Burroughs, were exhibited, along with notebooks and related written and published material, in cabinets — the scrapbook collage pages were reminders that Gysin was not principally a collage artist at all, and that in fact he had great reservations about making pictures with that technique. Collage was a tool for Burroughs and Gysin in their systems collaborations, but it wasn’t until the Beaubourg and photo-grid series of the 1970s that Gysin employed it whole-heartedly in his art. Rather, the show revealed Gysin as a draughtsman and painter whose work conjures evanescent, transient optical and psychic experiences, a vision which ranges from transcendent detachment to possessed, splenetic attack. His art uses his calligraphic touch and layered processes to communicate the scattering, shattering, and dematerialization of perceptual phenomena and the flux of states of consciousness — seeking the creation of exemplary embodiments of transcendent moments and their dispersal, an art ofapprehension in every sense. They are not “illustrations” of drug experiences, surreal depictions or visually contrived approximations of the hallucinatory. The pictures create continually shifting, flickering apparitional fields, both suggesting and stimulating changing states of consciousness — optical phenomena inseperable from psychic conjuration. Those tiny dancing figures of light, the “little people” of psilocybin and kif can be seen in gestural flashes and twists, implosions and radiations of color. The skyscraper becomes a grid, the stroke of paint a flower pistil, and back again, the painted image emerging and disappearing through a ghosting figuration which pulsates through rhythmic brush strokes, while the speed, time intervals, internal rhythms and velocity peaks of Gysin’s calligraphy are breathtaking. It’s the work of a “psychic assassin,” for sure, pushing extreme states including the alienation effect of the disembodied and mechanistic, but beneficent, too — seductive, poignant and tender. The show included a room where Gysin’s “Expanded Cinema” of scratched color slides was projected, another with several spinning Dreamachines, and Balch’s film Towers Open Fire was also shown, so that Gysin’s paintings were placed, as they should be, in relation to his multimedia work. People rushed in to sit around the Dreamachines, and they knew exactly what to do. It was entrancing.

The exhibition “Brion Gysin: Dream Machine” was curated by Laura Hoptman who has also written an essay, “Disappearing Act: The Art of Brion Gysin,” for the accompanying book, which she has edited, Brion Gysin: Dream Machine. The book, like the show in its New York incarnation, attempts to situate Gysin’s work in contemporary art practice as well as in 20th century art history — though Hoptman is aware that Gysin’s art was a psychic, magical exploration that does not fit convenient formal and stylistic categories. The title of the retrospective and the book separates “Dreamachine” back into its two component parts, though that conjoining was more than a marketing ploy, a brand name for a device — it was itself part of Gysin’s hybridization technique. The beginning of one word is found in the end of another and in their seamless coming together a profound idea is given perfect verbal form — the merging of two apparently contradictory states of being which are linked by their bypassing of human control. The autonomous device operating outside the human body and beyond human control passes into the dream as psychic event which takes over the helpless sleeper. This is the meaning of the Dreamachine as Soft Machine — the giving up of control, becoming an agency for the transmission of images, the Dreamachine triggering the hidden genetic permutations of the psyche. Hoptman distinguishes Gysin’s work from the calligraphic and the grid artists of his time — he could not be categorized, he did not belong to those schools to which his own work bore only a surface resemblance. He was playing a game with certain stylistic and formal tendencies, including action painting and Tachisme and kinetic art — whilst subverting these, doing something quite different and working undercover. The book includes homages by today’s artists who have been directly influenced by aspects of Gysin’s diverse, complex oeuvre, and it is significant that Gysin’s subterranean, heretical influence now seems more vital than so many of his contemporaries. This retrospective and the accompanying book are admirable attempts to re-evaluate Gysin’s work, and to recontextualize it in regard to certain contemporary art practices, and this has been long overdue. Even so, there is the still misunderstood, largely uninvestigated work of Gysin and Burroughs’ Third Mind. A number of the scrapbooks were presented in display cases at the exhibition, and examples of the grid collages are reproduced in the book, but the Third Mind cannot be accessed or understood through this kind of presentation alone. Gysin and Burroughs’ project was determinedly ant-art, anti-literature, and also anti-collage-as-art, and those who seek out the political, technological, esoteric Third Mind techniques and strategies will do so in ways which bypass, necessarily, the obfuscation and misdirection of cultural analysis and specifically artistic readings. The Third Mind is absolutely not reducible to a collage text or artwork — it was very much more than that, and even at the textual level, the way the scrapbooks work goes beyond such reductive formalist description. Telepathy, scrying, machine production, drugs, magical invocation, cut-up and other techniques, along with strategies related to photographic illusion must be explored through experimental material practice — which has nothing to do with being shown in a gallery or recorded on film or selling a book, and not only because of the transitory, inchoate and risky nature of the phenomena and processes involved. The idea that Gysin’s artworks from the late 1950s onwards can be separated from his Beat Hotel experiments is unsustainable since their development was reciprocal, entirely enmeshed, and this symbiosis continued after Gysin and Burroughs left the Beat Hotel — the discoveries informed both men’s work for the rest of their lives. At the same time, the artefacts and working documents accrued in the process of Third Mind research may be exhibited, and studied as formats and procedures linked to Gysin’s artworks, and to the texts of both men, while Gysin’s beautiful paintings may themselves be recognized for their originality and their significance in art history, but this kind of critical activity will only take you so far because “theoretical understanding,” in the case of the Third Mind, is a complete contradiction in terms — the process is experiential, it is of the unknown. If this is a problem for criticism, it’s also an opportunity — to explore Gysin’s art by actually engaging with the processes and techniques of the Third Mind which made Gysin’s work possible. Terry Wilson has written about attempts “to neutralize and assimilate a lifetime of psychic power into three-dimensional financial manipulative areas… to neutralize, assimilate, destruct. . .,” and the “contextualization” of Third Mind artefacts as historical manuscripts or artworks by any other name risks losing the essential purpose of Gysin and Burroughs’ work. Their own book, The Third Mind, was not what they had hoped for, the outcome a perfect example of market forces at work, while the original blueprints and “field recordings,” and the teachings passed along to a few, call for further research and action rather than the promulgation of “ideas” or the validation of existing knowledge. Despite the fascination and beauty of certain Third Mind works, they are technical plans, resource materials, spin-offs of a way of thinking and being in the world which cannot be aesthetically or intellectually recuperated. Continue reading

In a film like 2001, a project that started with the explicit purpose of investigating the possibility of extraterrestrial life, it comes as no surprise that Kubrick decided very soon in the production to tackle the problem of how to actually depict the extraterrestrials themselves.

Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke had met for the first time in April 1964: by the last months of that year the director had already set up a team working on hundreds of drawings about possible E.T. shapes – his wife Christiane was on board as well and worked on preparatory drawings – and in late 1965, the young and recently hired collaborator Anthony Frewin joined the team, researching on modern sculptures, paintings of German artist Max Ernst and modern art in general to try different ideas. (Here’s a detailed account by Frewin about his appointment to the movie and about Kubrick fondness of Ernst; thirty years later, Ernst’s influence resurfaced in a Ian Watson interview about the making of the movie that turned out to be Spielberg’s Artificial Intelligence).

Some of those eerie alien landscapes are available, as ‘bonus materials’, in the DVD edition of2001 issued in 2007 (and captured in screenshots in these three fine websites); here’s an example of the material and a comparison with a famous painting from Ernst:

Another reason for an early start in the quest for a credible alien came from the script evolution. Arthur C. Clarke gives us an interesting hint about the many ideas pursued and abandoned; starting with an entry in his diary dated October 6, 1964, reproduced in the bookThe Lost Worlds of 2001:

Have got an idea which I think is crucial. The people we meet on the other star system are humans who were collected from Earth a hundred thousand years ago, and hence are virtually identical with us.

The earliest outline of the story drafted by Kubrick and Clarke featured the discovery of a extraterrestrial artifact not in the beginning of the story (as in The Sentinel, the 1948 novel that was chosen as a basis for the movie) but as the climax;

Before that, we would have a series of incidents or adventures devoted to the exploration of the Moon and Planets. […] The rest of 1964 was spent brainstorming. As we developed new ideas, so the original conception slowly changed. “The Sentinel” became the opening, not the finale.

So, now that the plot had to focus on an early meeting of alien and men that had to take place on earth, the script had to feature an explicit description of the alien. In a draft from 1965, the main alien character even had a name: Clindar; straightforwardly borrowed by Clarke from his old novel Encounter in the dawn (1954), originally collected in the anthologyExpedition to Earth.

Although not included in the series of novels whose rights Clarke had sold to Kubrick as a basis for the 2001, Encounter will end up giving the first part of the final movie its basic structure: Clindar is a very human-like alien who “could pass for an human with some surgery” and he’s basically an anthropologist that helps the struggling ape-men, showing them, among the other things, how to kill a hyena with a bone. Clearly, Clindar’s function is the same of what the monolith turned out to have in the finished movie: he’s a catalyst for the potential of the human race.

Slowly, Kubrick and Clarke decided to move the actual meeting of aliens and humans to the climax of the movie, in the final scene after the Stargate – basically trading places with the appearance of the alien artifact; and the monolith, that at this stage had already appeared on the moon as a pyramid as in The Sentinel, would take the place of the aliens as catalyst/teacher on the prehistoric earth. Continue reading